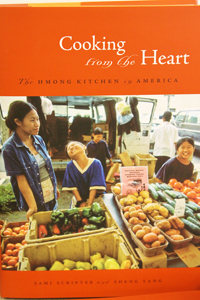

Cooking from the Heart: The Hmong Kitchen in America

Friday, May 29, 2009

Lori Writer / Heavy Table

Lori Writer on May 22, 2009

“In the isolated mountain villages of their Laotian homeland, cooking was… the stuff of tradition, not the written word. Good Hmong cooks learned from their elders which ingredients to use, and how much of each, by sight, feel, and taste. Recipes were never written down and followed ‘to the letter.’ Cooking, like other Hmong arts and crafts, came ‘from the heart.’”

(From Cooking from the Heart: The Hmong Kitchen in America by Sami Scripter and Sheng Yang, published this month by the University of Minnesota Press ($29.95; 248 pages, hardcover with color photos, available at Hmong ABC Bookstore at 298 University Ave. W in St. Paul).

Katie Cannon / Heavy Table

Sheng Yang, and her parents and four siblings, immigrated to the United States — first to Kentucky, then Oklahoma, and then, Oregon — in 1979, when she was nine. Sami Scripter, married and tending to her growing family, was Sheng’s neighbor in Portland, OR. Sami worked as an educator at Sheng’s elementary school. Speaking to a small audience at the Hmong Cultural Center in St. Paul on Thursday, Scripter recalls, “One year you didn’t know what Hmong was, and the next year a quarter of the children in school were Hmong.”

Yang says that over the years their “two families have become almost one.” Scripter adds, “We got to know each other the way neighbors know each other.” They gardened together in the Scripter’s backyard using seeds Sheng’s mother had carried from Laos and Thailand. Sami taught Sheng and her mother how to preserve raspberry jam.

As a sixth grader, to improve her English, Sheng lived with the Scripters, rooming with Sami’s daughter, Emily, in a bunk bed Don Scripter built for the two girls. “Sami learned to cook rice the Hmong way using an hourglass-shaped pot and woven basket steamer, and Sheng learned how to make… meatloaf, baked potatoes, and peach pie,” the authors write.

Out of their friendship and years of cooking together and jotting down ingredients grew Cooking from the Heart, which is as much a “celebration of Hmong culture as it is lived in the United States” as it is a cookbook, Yang says. “We wanted to remember who we are… to store the heritage and cooking and pass it down to our children to keep and treasure for years to come.” Scripter adds: “There are many ways of remembering: the Hmong oral tradition is one way; the paj ntaub [Hmong embroidery, pronounced "pa dao"] that women sew is another way. And a cookbook is a way.”

Katie Cannon / Heavy Table

In their book, Scripter and Yang touch on eating etiquette and table settings; herbal medicine and healing traditions; and weddings, New Year’s, and funeral customs, and the role food plays in each. Of funerals, the authors write: “The haunting notes of a Hmong bamboo pipe, called a qeej [pronounced keel, pulling your lips tight and speaking almost from your throat], and the rhythmic tum, tum, tum of a special wooden drum constructed exclusively for the service pervade the atmosphere of a traditional funeral.” (Txu Zong Yang plays the qeej and performs the complex dance movements in the photo to the right).

“Three times a day a gong signals meals for all attendees. The deceased is symbolically fed. Then everyone attending the funeral is also fed… It is common for a family to have one or more cows or buffalo butchered and cooked each day to feed the crowd. Cauldrons of boiling meat… are prepared. Mountains of rice are steamed… As with many rituals and events, food is an essential component contributing to the solidarity of Hmong people.” The authors devote an entire chapter, “Cooking for a Crowd,” to dishes commonly served at Hmong gatherings.

Katie Cannon / Heavy Table

The book is sprinkled with Hmong poetry and essays, such as May Lee-Yang’s “The Year My Family Decided Not to Have Papaya Salad and Egg Rolls for Thanksgiving,” that convey the joys and challenges of growing up Hmong in America.

One side-bar, Ka’s Journal, tells the story of a Hmong woman who, unbeknownst to her family, painstakingly recorded the events of her life, including drawings of Hmong cooking tools, in a spiral-bound notebook she kept in a basket under her bed, wrapped in a skirt. Her children discovered Ka’s journal only after her funeral.

Rather than try to document Hmong cuisine in general, Scripter and Yang focused on “what individual Hmong cooks do,” coaxing recipes out of family and Hmong cooks around the US. Recipes include Saly’s (Yang’s mother-in-law) Rice and Corn Pancakes; Der’s (Yang’s sister) Egg and Cucumber Salad; and Chee Vang’s (a woman who lives in Denver, CO) Stuffed Chicken Wings.

“We wanted to write about Hmong cooking everywhere,” says Scripter. “We cooked in other people’s homes.” The dish that everyone loves, in spite the “startling array of differences” in the ways it’s prepared, says Scripter, is Chicken Curry Noodle Soup or Khaub Poob (pronounced kah-poong). “Some put quail eggs in it. Some make it with garlic, some without… It’s all very good.”

The book includes an extensive discussion of cooking tools, packaged ingredients, and vegetables and herbs used in both cooking and healing. Rather than trying to gloss over ingredients that may seem out of favor, such as MSG, or unfamiliar to non-Hmong or Hmong who have grown up in America, Scripter and Yang take the challenge head-on. Of Traditional Beef Soup, “cow-poo soup,” made of beef stomach, intestines, and organ meat, they write: “Contradicting its name, the soup is made of healthy ingredients and is very nutritious. However, this dish may not be for people who are one or more generations away from having to eat whatever is available in order to live.”

“We wanted to write about Hmong cooking everywhere,” says Scripter. “We cooked in other people’s homes.” The dish that everyone loves, in spite the “startling array of differences” in the ways it’s prepared, says Scripter, is Chicken Curry Noodle Soup or Khaub Poob (pronounced kah-poong). “Some put quail eggs in it. Some make it with garlic, some without… It’s all very good.”

The book includes an extensive discussion of cooking tools, packaged ingredients, and vegetables and herbs used in both cooking and healing. Rather than trying to gloss over ingredients that may seem out of favor, such as MSG, or unfamiliar to non-Hmong or Hmong who have grown up in America, Scripter and Yang take the challenge head-on. Of Traditional Beef Soup, “cow-poo soup,” made of beef stomach, intestines, and organ meat, they write: “Contradicting its name, the soup is made of healthy ingredients and is very nutritious. However, this dish may not be for people who are one or more generations away from having to eat whatever is available in order to live.”

Source

0 hlub:

Post a Comment